Every Man, Woman and Child in Guyana Must Become Oil-Minded – Column 159 – June 6, 2025

Exxon’s 2024 Financial Statements

1. Overview

Earlier this week ExxonMobil Guyana Limited (EMGL) summoned the Guyana press to the launch of its2024 Annual Report. Two conditions: only questions on the financial statements would be entertained and the number of questions strictly restricted. Like one of its junior partners Hess, the results for 2024 are staggering, and its profitability measures more that double the Exxon group as a whole. Guyana’s Stabroek Block now joins Kohinoor (India circa 1300) and the Cullinan (South Africa 1905) to create an imperial trinity of exploitation of plunder acquired under unequal terms, adorned as triumph and defended by the exploiter and the exploited.

Unusually for a branch or what is called an External Company incorporated in The Bahamas, Exxon publishes a glossy annual report with more photographs than our own public companies. It presents a glowing picture of economic transformation and partnership with the people and the Government of Guyana. However, beneath the positive narrative, the report glosses over – or buries – critical details about the tax treatment under the 2016 Petroleum Agreement, including the government’s controversial obligation to pay Exxon’s taxes.

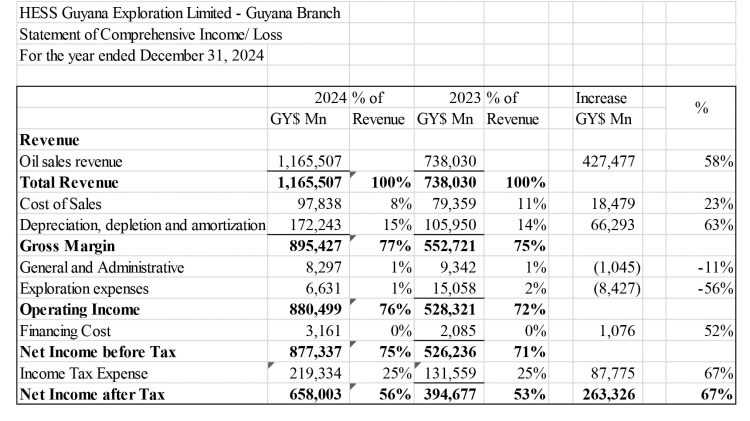

One cannot help but describe Exxon’s statements as a deliberate web of deception – as they have been since the overstating of pre-2016 costs. The Business Service Manager announced a 60% increase in revenue while the actual figures show 56%, a result of how far they will go to conceal the fact that they do not pay taxes – Guyana pays it on their behalf. The difference between the 56% shown above and the 60% announced is as a result of adding the tax shown as deducted – which they do not pay – to the revenue which in 2023 was shown as “includes] non-customer revenue related to Article 15.4 of the Agreement”. SHAME on the Company, SHAME on the Government and SHAME on our accounting profession which never calls them out.

As a percentage Production cost has remained at 4% of revenue, Exploration cost 1% of Revenue, Lease Interest 3% and Royalty 2%. The big cost is Depreciation and Amortisation of $301,849 Mn which makes up 17% of Revenue.

One titillating statistic: Exxon’s total comprehensive income for the year – after accounting for taxes which the Government pays – is close one and a quarter trillion dollars. It took Guyana fifty-nine years before its budget reached one trillion dollars. Exxon earns in income for its foreign shareholders substantially more in less than ten years.

Thank you Trotman, thank you Jagdeo and thank you Ali!

The Balance Sheet

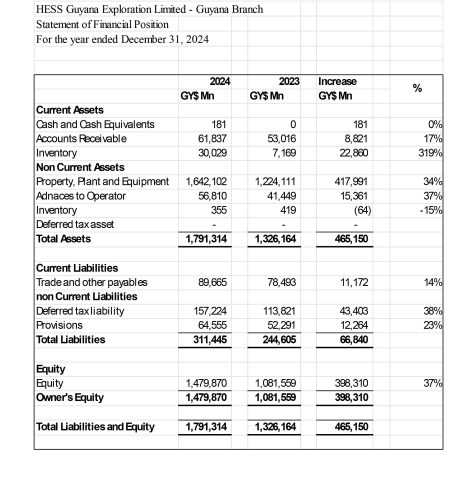

The Balance Sheet is sometimes called the Statement of Affairs or Statement of Net worth or simply Statement of Assets and Liabilities. The table below is a (slightly) summarised restatement of the audited financial statements. The figures are stated in Guyana Dollars but for convenience, the table is prepared in millions of Guyana Dollars.

Highlights

Expenditure on Wells and Production facilities accounts for $605,000 Mn, of which a significant portion comes out of Work in Progress. Deferred and Trade Receivable has increased by 90% and requires some explanation. Deferred Receivable represents amount due from Joint Venture Partners from cash calls and also non-customer revenue which is probably the amount it expects to receive from the Government of Guyana to meet its tax obligations. An amount that will be cleared in four months’ time is hardly a deferred receivable but that is how flexible and creative Exxon is.

What is even more astounding is the amount of $352,681 Mn. described as amounts due from the Home Office to fund Petroleum Operations. The average amount due from the Home Office over the year is just short of $400,000 Mn. That’s an embarrassment of wealth.

What makes this situation even more incredible, is that in 2024, this 45% interest in the Stabroek Block – our Stabroek Block – earned Exxon’s 45% interest a whopping $1,255,300 Mn, or $1.2 Trillion. That is more than 150% that Guyana is likely to earn by way of income through the Consolidated Fund.

The tax mystery

The mysterious tax arrangement is causing all kinds of contortion and deception among the oil companies. Here is a comparison of the note on tax charge in 2024 compared with 2023.

| 2024 | 2023 |

| Note 7 – INCOME TAX EXPENSE Income Tax Expense is recognised in respect of taxable profit calculated on the basis of the income tax laws of Guyana that have been enacted as of the date of these financial statements. | Note 7 – INCOME TAX EXPENSE Under Article 15.2 of the Petroleum Agreement, the Branch is subject to the Income Tax Laws of Guyana with respect to filing returns, assessment of tax, and keeping of records. Under Article 15.4 of the Petroleum Agreement, the sum equivalent to the tax assessed on the Branch will be paid by the Minister responsible for Petroleum to the Commissioner General, Guyana Revenue Authority and is reported as non-customer revenue. |

Conclusion

ExxonMobil is the first Branch entity that produces an Annual Report. It is shiny, designed to present an image of corporate responsibility and national partnership. That is a trap. Exxon knows how to play gullible politicians like those they have met in Guyana. In the Coalition, they met amateurs, dazzled by oil, eager to please and out of their depth. In the PPP, they confuse the bright ones out of renegotiation, ring-fencing, an independent Petroleum Commission and into insider dealings, fears and cowardice. Exxon did not need to change its strategy. Just the faces across the table.