Every Man, Woman and Child in Guyana Must Become Oil-Minded – Column 162 – 20 June 2025

Introduction

Columns 159 – 161 examined the individual income statements of each Stabroek Block contractor in detail. Today’s column shifts focus to analyse the combined results of the three entities, providing a broader perspective on the collective financial performance and strategic positioning of the consortium operating Guyana’s most significant petroleum asset.

Before doing so, however, let us have a brief look at a report in the Kaieteur News of 17th. June quoting Mr. Vickram Bharrat, Minister of Natural Resources on the state of relinquishment provisions on the Petroleum Agreement for the Kaieteur block.

The Kaieteur block agreement was signed with Exxon in April 2015 with a four-year initial exploration period that should have expired in April 2019 and two three-year renewals to 2025. At the end of the initial period (to 2019) the company should have relinquished 45%, a further 20% in 2022 and the balance in 2025, except for any area for which a production licence is issued, or any extension for cause. However, according to a statement from the company an extension was granted to February 2026 on the grounds, cited by the Minister, that the government was “compelled” by law to do so. Such a statement reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the Production Sharing Agreement or deliberate deflection of responsibility.

That statement is false and would not be made by anyone with a passing understanding of Article 4.1(e), which states, unambiguously, that the Minister “may” extend exploration periods upon a showing of good cause – making his claim of legal compulsion demonstrably false while revealing dangerous regulatory weakness.

The danger is aggravated by the failure of the company to meet the conditions required to qualify for extensions. Despite only one sub-commercial well being drilled since 2015, no mandated relinquishments have occurred despite deadlines passing in 2017, 2019 and 2022. Notably, ExxonMobil simply walked away rather than meeting drilling commitments – failures which should disqualify from any extension eligibility under any competent contract administration.

This regulatory capture traces back to the Jagdeo Administration’s overly-generous force majeure relief for the entire 26,806 sq KM Stabroek Block following the Suriname vessel boarding incident – a vast distance from actual operations. With Jagdeo now heading petroleum policy, this permissive approach has become institutionalised, creating an environment where industry wishes consistently trumps national interest while the government rubber-stamps requests without rigorous scrutiny.

The PPP/C Administration has watered down its campaign commitment, first to renegotiate the 2016 Petroleum Agreement, then to better contract administration and reform, then to sanctity of contract and the latest, that the Minister is legally compelled to extend the duration of a petroleum agreement. To sum up. The PPP/C Administration has been unable to cross the lowest of the low bars that it has set itself.

That the individuals responsible for the petroleum sector are so poorly informed must be a serious cause for concern. Note: This Agreement was signed days before the 2015 elections.

Now, back to those financial statements.

Challenging presentation of annual reports

Nearly eight years after the signing of the now-infamous 2016 Petroleum Agreement, it is clear that neither the foreign oil companies nor the Government of Guyana have any real interest in accountability. While the country’s leaders boast about revenue inflows, the foundational elements of transparency – consolidated project accounts, proper cost audits, and consistent financial reporting – are glaringly absent or deliberately obfuscated. The Guyanese people remain in the dark as to whether they are receiving even the bare minimum promised under the Agreement, including their so-called 50% share of profit oil.

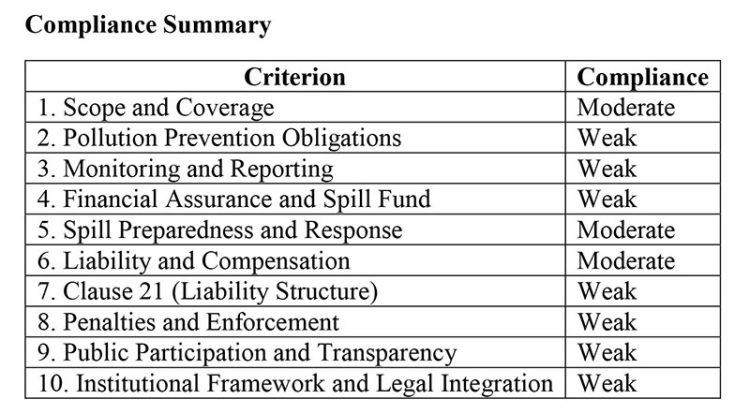

Annex 2 of the Agreement, which sets out the companies’ reporting obligations, is weak and ineffectual. Reports are submitted solely to the Minister, with no legal requirement for publication or independent audit. There is no consolidated field-level financial statement, no disaggregated cost data, and no mechanism to ensure that the separately published financial statements with limited, inconsistent, and opaque information is accurate, reliable and timely. As a result, neither Parliament nor the public can verify whether the oil companies are overstating costs or underreporting profits. To correct this, Government should mandate publication of all Annex 2 statements, require independent project audits, and adopt the EITI standard in full.

What makes matters worse is the inconsistent, and in some cases misleading, financial disclosures by the oil companies themselves – all audited by the same firm. Only CNOOC acknowledges the joint operation classification under IFRS 11while Hess and Exxon remain silent on the nature of the arrangement. On taxation, CNOOC correctly states that the Government pays the contractor’s income taxes out of its share of profit oil. Exxon evades the issue entirely, while Hess claims to be subject to a 25% corporate income tax, even producing a tax computation – a misleading practice at best, and a dishonest one at worst.

The contents of the Income Statements are all different. Even the reporting currency lacks consistency. Hess reports in U.S. dollars, CNOOC in millions of Guyana dollars, and Exxon in Guyana dollars. Then there are differences in treatment and disclosure of items like royalties, retirement obligations and Decommissioning and Royalties. Such differences frustrate comparability, undermine audit quality, and suggest that the companies are dictating the terms of disclosure to their auditors – not the other way around.

Since the Government pays the corporate tax of all the companies from its share of profit oil, there should is no differential treatment. Yet, the effective tax rate of tax on the income earned by each of the companies differs significantly. This is not helped by three divergent disclosure notes, the reason for which is far from apparent. Even more troubling is the illusion of equity embedded in the so-called 50/50 profit-sharing arrangement. The financial statements of the oil companies show multibillion-dollar earnings while Guyana’s share remains comparatively meagre. The ratio for the year 2024 and cumulatively for the five years to December 2024 is in excess of 5:1.

Government

But the Government too is guilty of opacity, if not deception. Public filings of the Exxon and Hess in the US suggest that the Government issues them with proper tax certificates confirming the discharge of their Guyana tax obligations. See Article 15:5 of the Agreement. Two problems: no money is paid out of Guyana’s share of profit oil and there is no oil company taxes paid into the Consolidated Fund. The rules of EITI, the principles of accounting, and transparency require full, complete and comprehensible disclosure. Whichever accounting route is followed – whether the taxes are deducted before transfer to the Natural Resource Fund, or after – the outcome is equally misleading.

Because the NRF has a significant component of intergenerational funds, the Government has an interest in window-dressing the balance – to make it seem better than it is. It is therefore comfortable manipulating the balance by not reflecting the amount of the tax required to be paid on behalf of the oil companies. The oil companies for their part, are not concerned about the small matter of accountability and transparency, or whether the Government manipulates the NFR or whether Tax Certificates are issued for money not received.

Compounding these financial distortions is the government’s ongoing failure to enforce one of the few clear powers it has under the Agreement: the relinquishment clause. Exxon and Co. was required to surrender 20% of the Stabroek Block contract area nearly a year ago. Instead, we are told the Ministry of Natural Resources is still “finalising” the areas to be given up. See also the introductory note on the Kaieteur Block for evidence of the wider incompetence and laissez faire attitude to see how our marine petroleum assets are managed.

Next week, we will close out on the financials by looking at the companies’ aggregated balance sheets and the state of the Natural Resource Fund.